André Parente and Kátia Maciel

Site specific installation

2015

Noche es dia, by Katia Maciel and André Parente, La Tertulia Museum (Cali, Colombia, December 2015/April 2016), curated by Alejandro Martin Maldonado

Noche es dia (Night Is Day) by Katia Maciel and André Parente: A Reflection on Living

This exhibition arose from a very particular challenge: the La Tertulia Museum in Cali, where I work as a curator, received last year an old mansion in the city as a new space: the Casa Obeso Mejía. The couple Antonio Obeso and Luz Mejía lived there throughout their entire 73-year marriage, and there they died within a short time of each other. They never had children and for several years they decided that they wanted to donate the house to the city, for cultural activity.

A year earlier, we had met Katia Maciel and André Parente in Cali, both of whom had come to teach a course on cinema and contemporary art in the Documentary Specialization program at the Universidad del Valle. Common interests soon arose: cinema and its current transformations, literature, philosophy, mathematics, poetry. When I saw their works, the subtle use of technology, the understanding of film grammar and video tools, and the programming to write minimal and powerful poems caught my attention. In particular, I was interested in the different ways of thinking about space (the different notions of distance) and how it is transformed by digital technologies.

I had studied mathematics and arrived at art through philosophy. Since I had always been a cinephile, it was not surprising that I soon found myself on common ground with André and Katia. After meeting a few times to talk, it became clear that we would like to do a project together soon.

The occasion came with the Casa Obeso Mejía. It is one of those big houses, the ones that made passersby ask themselves what they could find inside: due to its wide spaces, the luxurious life of its inhabitants. But it was by no means easy to think of an exhibition for such an architecturally, historically, and emotionally charged space. An initial idea was to open the house as it is, with all of its objects. However, it was a risk that the house would remain, for the common public, linked to the history of its owners. Somehow, the museum had to “take care of” the house, turn it around, open it to the public, and at the same time, show what could happen in it, which made the house come to be part of the museum. So the challenge was to think of the house based on the museum.

2. The Idea: An Exhibition about the Couple

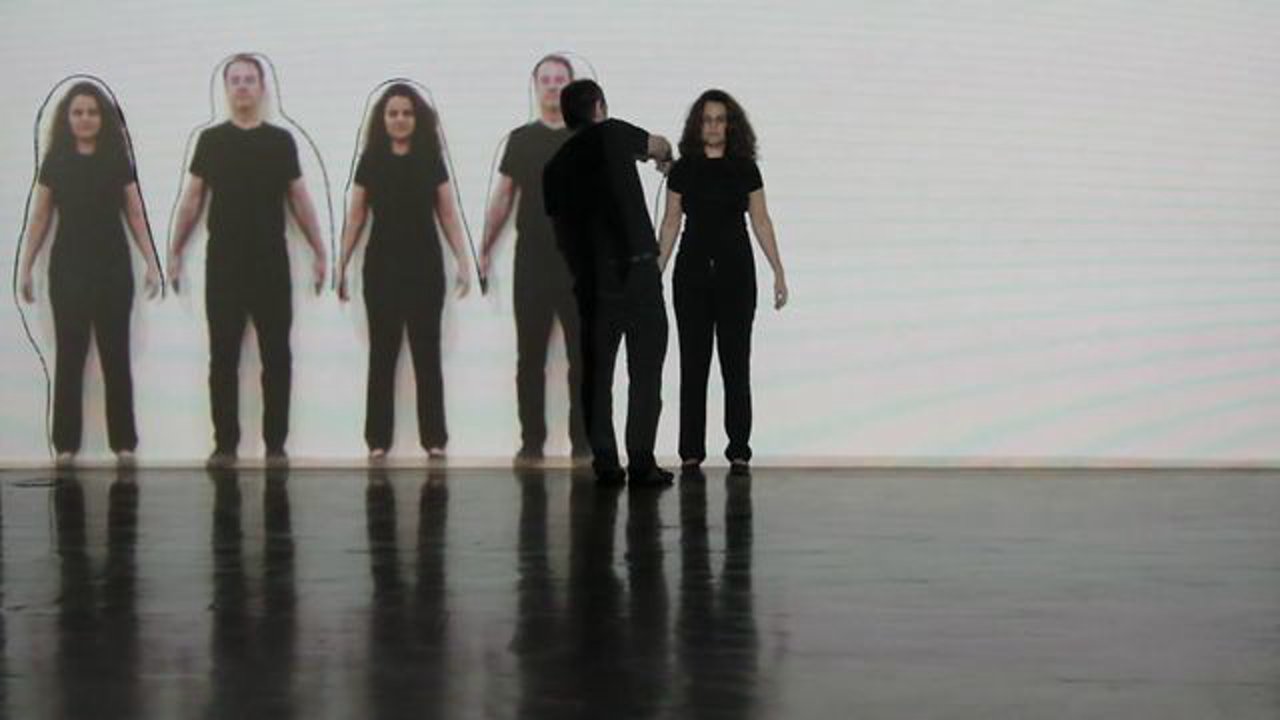

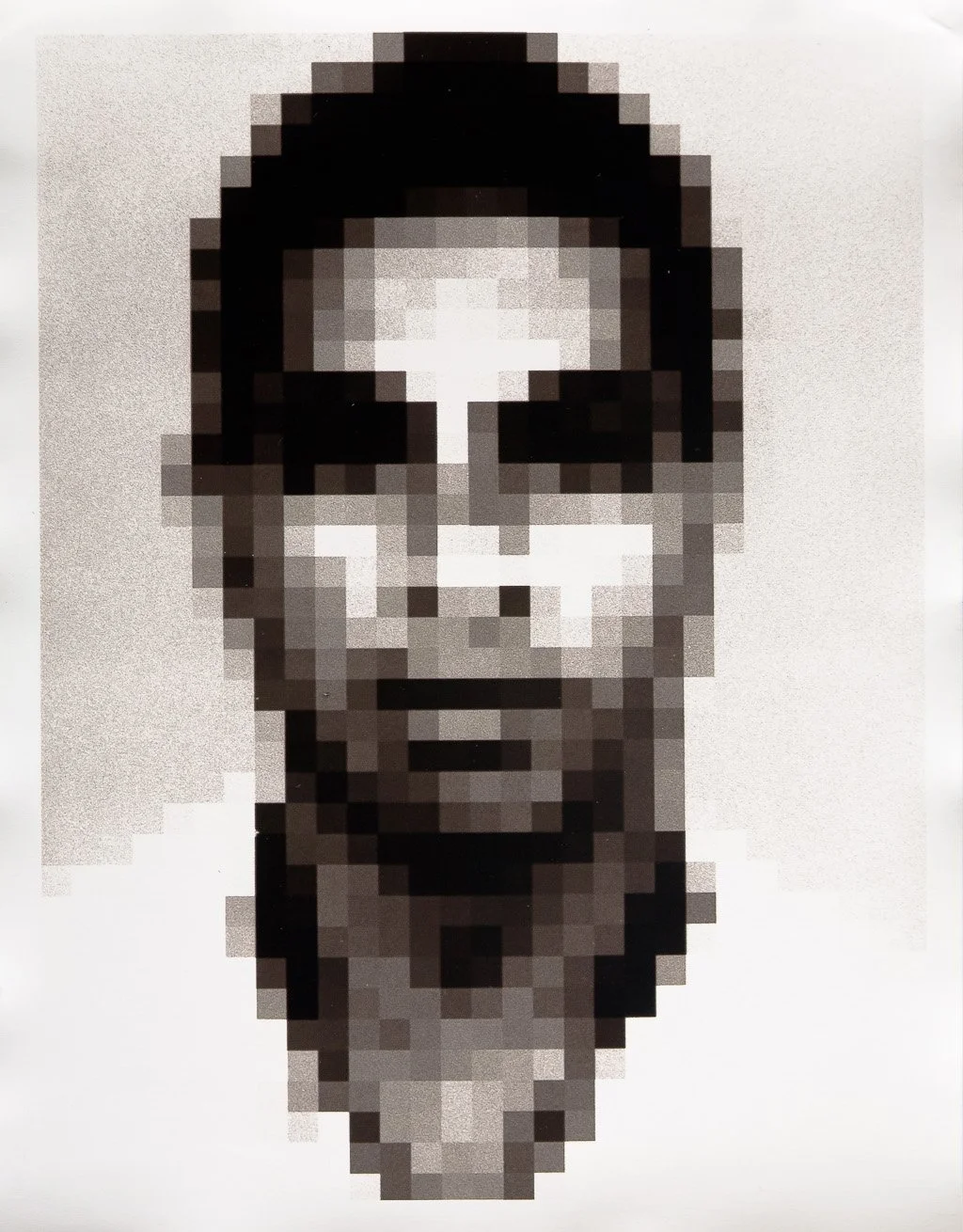

A video by André Parente, Estereoscopia (2006), is what gives me the key to the exhibition. It is a work from 2006, and it is the first in which Katia and André both appear as protagonists in one of their works (they will later appear together in many others of which they will be co-authors). The video begins with a close-up of Katia’s face, which is actually a zoom of a photo of her in the Botanical Garden of Rio de Janeiro, and when enlarged, it does not lead us to see the pores of her skin, but the elements of the digital image, which in this case is not made of pixels, but of multiple faces of André. Continuing the zoom, at the same pace, this time approaching André’s face, will lead us in the same way to Katia’s face, now creating the loop. We are then faced with a particular fractal in which Katia’s face is made of small images of André’s face, which in turn is made of small images of Katia’s face, which in turn…

And meanwhile both of their voices, taking turns, presented us with:

I want to see / What you see of me / Inside you

I want to see / What you see of me / What I see of you / Inside me

I want to see / What you see of me / What I see of you

Of what you see of me / Inside you...

Parente manages to play a double game with cinematic language. On the one hand, he transforms the most classic cut, the shot/reverse shot, into a continuous movement. And at the same time, he turns a looking game, a key to a meeting of two (the starting point of any relationship), into a series of Russian dolls, in which we have one doll inside another, since now each face has a double role as a face that looks, and a look that is a face. And as a contemplated face, what is presented to us now is a state of awareness of the one who looks.

In this video, what for me is one of the fundamental enigmas of the possibility of love and life for two has been condensed: how does this idea that one has of the other relate to the real other? What is the effect on others of the images that we have of them? How is this mismatch between image and reality, instead of being an impediment, what makes the couple real?

Then I thought about the enigma of the Obeso Mejía couple, a question that inhabited the whole house. I wanted to analyze the experience of those of us who entered there and who, based on the spaces, objects, and photos, tried to imagine something of their lives.

I decided that the exhibition would be precisely about the mystery of the couple. About the ways that the idea of marriage is linked to coexistence, to the space of the house. And I was going to contrast these two couples: Obeso and Mejía, Parente and Maciel. I was going to invite this new couple from Rio de Janeiro, who have such a different relationship, who grew up in other times and who had relations in other places, to intervene in the spaces of the couple from Cali.

3. The Question: Inhabiting Spaces

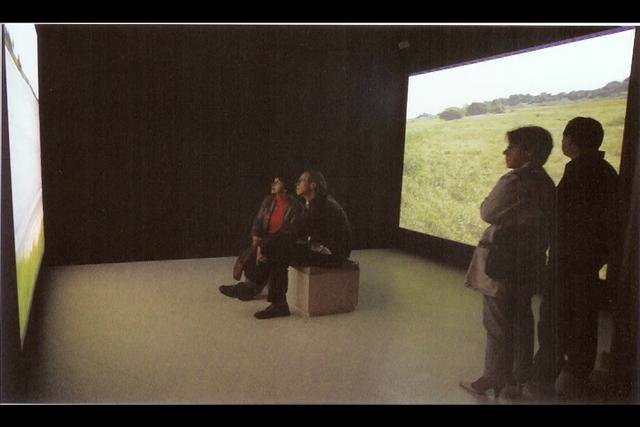

What would come next would be the process of choosing the works and the places in the house where they would be installed. The idea was to make use of most of the spaces: the hallway, the kitchen, the dining room, the living room, the bedrooms, the dressing rooms, the bathrooms. Success would consist in choosing the best work for each space, making a back-and-forth work, which involved carefully reviewing the complete work of both artists, searching for which works should be included and where.

All of this happened in a very rich internet relationship, which included hundreds of emails and a very interesting series of Skype conversations. The first thing would be to share the house plan and photos of each of the rooms, which in the cases of the kitchen, the bathrooms, and the dressing rooms were full of beautiful details and decorations. With a “guided tour” from a distance, explaining the nature of each space, and the conditions to be able to undertake this or that intervention. Something really cool that happened, and that was fundamental for creating a relationship, was that each of us gave a guided tour of our own space. Through Skype, I was able to show them my apartment, and each one did the same with his or hers, and thus, through the digital versions of our houses, we “opened up.”

And there I noticed something unique about the Brazilian couple, which is that they lived separately, building a marriage in different homes, with no common space.

Such a situation was the starting point for Infinito Fim (Infinite End – 2008), by Katia Maciel, an interactive video that builds an endless tunnel in front of the doors of each one`s apartment. The viewer is faced with a projected door and, upon approaching, it opens automatically, revealing a hallway with another door also opening, giving way to another hallway. This relation between the series of doors and the possibility of there being or not being a relation between the two of them echoes very strongly and forcefully with the work Estereoscopia. We could say that in each of these works, the two artists presented, from their point of view, their own theory of the couple.

We decided to install, in the living room, a passage room full of doors, which created an almost surreal atmosphere. There, one of the doors was replaced with a whiteboard on which we would project the video door.

And thus, one by one, we decided on the works for each of the spaces. The list, in a Google Docs file, would be modified with the correspondence. Just as there were easy decisions that never changed, there were others in which we kept going around and around until we agreed.

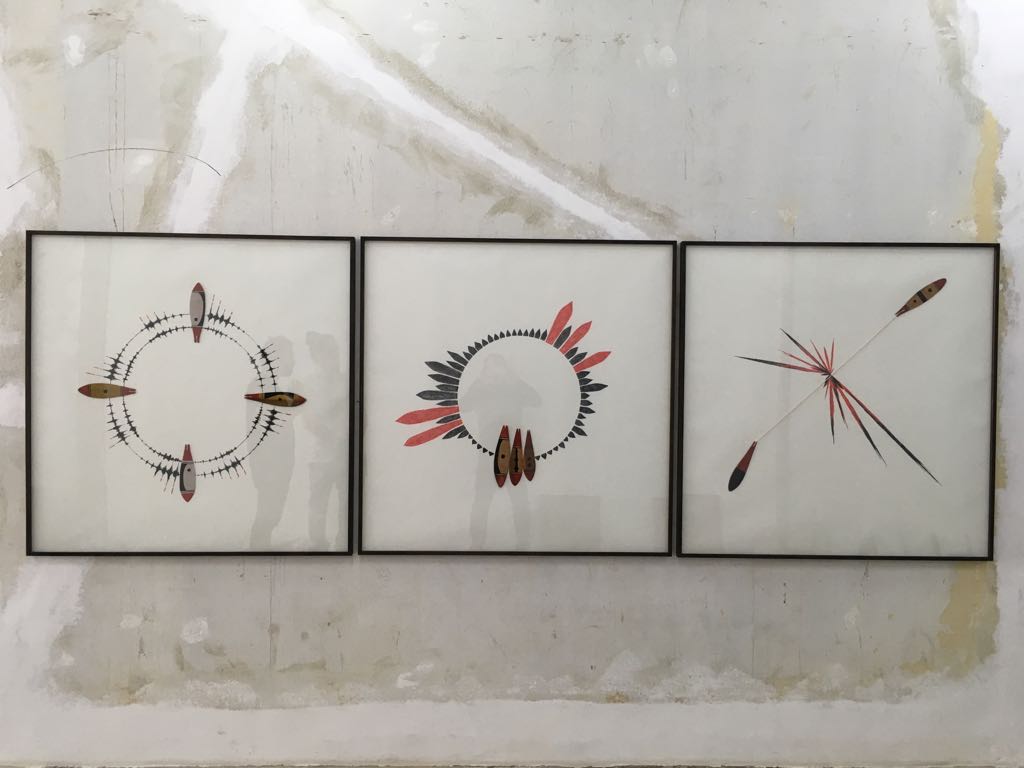

There were indisputable solutions such as using Maciel’s video Colar (Necklace – 2009), in the lady’s dressing room, projected onto an incredible dressing table made entirely of mirrors. In the video, Katia, in front of the mirror, puts on a whole collection of necklaces, one after the other, until covering her face, in a reflection on vanity and adornments, very much at play with a Luz Mejía who seems to be obsessed with mirrors.

In the list we tried to take stock of the works of each individual artist, also making room for collaborative work. In the couple’s bathroom, we projected onto the bathtub (over the water) a key video for the two of them, +2, in which they take turns lying on a pier that leads to the Lagoa da Conceição, joining each other, until losing themselves in the horizon. And in the dining room, which we turned into a kind of auditorium, we projected in a series the different experiments that the two conducted, playing with the couple idea, in the manner of “holiday videos” (a name that we gave to this set of videos), such as those that are generally designed for friends at night, back from a walk.

4. The Result: A Phantasmagoria

Since we did not want the operation to be one of canceling the house by closing all the windows, we decided that the exhibition would be open from 6pm to 9pm. Thus, the lights from the videos would be accompanied by the lights from the sunset until dusk, and viewers would be able to see the works and at the same time see the outside through the windows. The afternoon twilight would create the best environment for the video projections, on walls, doors, and furniture, to be charged with strength.

This exhibition was unique for the artists, since it was not held in the white cube of the museum as in the exhibitions that they had done until then. Going through the exhibition with Katia and André, once it was ready, conveyed a very special emotion, since they had never seen their works displayed in this way. Although their reflections on expanded cinema in various senses had led them to phantasmagoria, never before could the images be seen as phantoms animating a certain place, or rather, a house full of ghosts.

The exhibition was almost a miracle, in the extent to which it was necessary not only to assemble the works, but also to make the space available for exhibitions. On the day that the artists arrived in Cali, the main room, that of the couple, still had no roof. And they witnessed, with incredible patience, the house being rebuilt while the exhibition was being assembled.

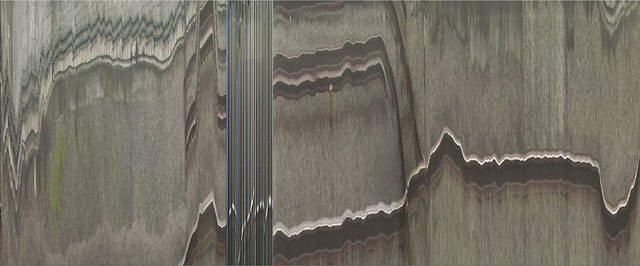

Precisely for this space, Katia and André created, in Cali, throughout the assembly, a new video: Marés (Tides – 2015), which would be projected onto the couple’s bed. In it, we would see the two artists sleeping, and in their dream, they would be covered and uncovered by the tide that rises and falls on the beach. That dream space, neither here nor there, which transposed them to the most private place of the Obeso Mejía couple, constituted the maximum possible transgression. The coming and going of the water and tide made the space breathe, and the light projected on the sheets filled all the air. The house was charged.

Noche es dia

La Tertulia Museum - Cali - Colombia - December 2015 / April 2016

Artists: André Parente and Katia Maciel

Curator: Alejandro Martin Maldonado

Installation Program: Julio Parente

Production: Felipe Tirado and Lina Rizo

Photographs: Juan David Velásquez